- Future Communication 17

- Future Health 8

- Future Media 10

- Future Technology 10

- Future of Business 10

- Future of Cities 8

- Future of Education 6

- Future of Energy 8

- Future of Finance 18

- Future of Food 4

- Future of Housing 3

- Future of Humanity 22

- Future of Retail 9

- Future of Sport 1

- Future of Transport 8

- Future of Work 8

- Future society 11

- Futurism 20

For a lot of my futurist career, blogging has been a major outlet. My posts are less frequent these days but occasionally I still use a blog post to organise my thoughts.

The archive of posts on this site has been somewhat condensed and edited, not always deliberately. This blog started all the way back in 2006 when working full time as a futurist was still a distant dream, and at one point numbered nearly 700 posts. There have been attempts to reduce replication, trim out some weaker posts, and tell more complete stories, but also some losses through multiple site moves - It has been hosted on Blogger, Wordpress, Medium, and now SquareSpace. The result is that dates and metadata on all the posts may not be accurate and many may be missing their original images.

You can search all of my posts through the search box, or click through some of the relevant categories. Purists can search my more complete archive here.

Will nuclear energy replace fossil fuels? #AskAFuturist

In the latest episode in my #AskAFuturist series, Tim Panton asks: "Will nuclear energy replace fossil fuels? If so, will it be fission or fusion?"

Tim Panton (@steely_glint) asks: “Will nuclear energy replace fossil fuels? If so, will it be fission or fusion?”This is one of those questions that is hard to answer accurately without sounding like you are trying to fudge it. Because the answers are ‘yes, but only some’ and ‘both, but not at the same time’. And also, ‘it depends what application you’re talking about’, and ‘over what time frame?’

One of many

The first challenge in answering this question comes back to one of the five major trends I track that I see popping up in every domain I examine: choice. We live in an age of low-friction innovation, where building novel solutions to problems is easier than it ever has been. That does not mean it is easy, but it does mean that the turnover of new technologies is faster, and that the variety of technological solutions is wider.The adoption of these technologies is also easier and cheaper. With lower barriers to entry, people can afford to experiment more. And with lower innovation and production costs, suppliers can afford to support smaller niches.The result is that there is rarely one answer to any problem. It is impossible to say that nuclear will replace fossil fuels because LOTS of things will replace fossil fuels. Indeed, they already are. Check out this chart from the IEA’s 2019 World Energy Outlook report: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/installed-power-generation-capacity-by-source-in-the-stated-policies-scenario-2000-2040This is specifically for the power generation market – electricity, in other words. What it shows is that coal consumption has flattened, and oil is down, while gas continues to grow. Meanwhile, solar and wind are on incredible growth trajectories. Hydro and other renewables are also growing. In the IEA’s projections, nuclear is fairly flat. This is all over a 20-year time frame with projected global energy consumption continuing to rise.

Fission flat

These projections seem plausible to me. We might hope to see a faster decline in gas and coal offset by even more dramatic shifts to solar and battery storage. This is possible with large infrastructure investment in those countries with highly centralised grids. Given the noises about economic stimulus investment in the UK and elsewhere, we might just see some of this. But it is hard to see the nuclear picture being anything other than (largely) flat.This is not because there will not be new nuclear. But lots of reactors in places like the UK and France are ageing and well beyond their original design life. So even large-scale development will only hit replacement levels. There is some hope for smaller scale nuclear systems that might fit well into a more distributed grid infrastructure as a back up to primarily renewable generation, or that could be clustered to replace coal or ageing nuclear plants. Certainly, lots of investors, including governments, think this idea has strong prospects. But it is hard to see it growing at a rate that makes it a serious candidate for replacing the majority of fossil fuel consumption, even just for energy generation.

Commercial fusion?

Meanwhile, fusion research continues to make slow progress. It is hard to see it hitting commercialisation at any real scale in the 20-year IEA time frame. Even if the model is proven, it is unlikely anyone in the west would be able to build out a reactor within another decade. China is a different matter and there, practical fusion power might be a valuable alternative to the country’s enormous reliance on coal. But still, it is hard to see it making a serious impact in the next twenty years.

Renewables

Meanwhile, solar, wind, hydro and tidal power advance apace. As does the storage technology to offset their intermittent feed. Done at very large scale, these projects require very large investment – the sort that takes years to assemble or that has to be underwritten by governments. But done at smaller scale, they can be rolled out relatively quickly and cheaply. This feels like the best bet for a lot of fossil fuel replacement.Roughly two thirds of grid energy consumption in the UK is in residential and commercial venues, where small scale renewables and storage might present an opportunity to shift away from grid power for at least a proportion of usage. The shift to electric vehicles means that these sources might also power a lot of our transport. Only in large scale industry like steel manufacturing does small scale renewables and storage feel less practical – though I would be delighted to be proven wrong on this. Perhaps here is the opportunity for small scale nuclear? Single or clustered plants could be used to provide consistent, clean(er) energy to major consumers and the surround areas.

Looking beyond

In the longer term, fission feels like a dead technology. It is cleaner than coal but still leaves a lot of radioactive mess behind that we don’t have a good solution for. I do believe we will one day crack the fusion challenge, allowing us to generate a lot of energy in a small space. But remember: however sophisticated the heat source, nuclear fusion would still be used to make steam to spin a turbine. This is the same way we have been generating power for 140 years or so. Even the Romans were using steam to make stuff spin. It feels a little old fashioned. The sci-fi nerd in me wants something solid-state, more like Iron Man’s arc reactor. But sadly no-one outside of the fictional universe knows how that might work.So, will nuclear energy replace fossil fuels? Yes, but only some.

#AskAFuturist: What have you been most wrong about in the past?

James Saye asked, "What have you been most wrong about in the past?" Answer? Lots, but always for the same reason: I got 'what' right but 'when' wrong.

The inspiration for this post comes from James Saye who responded to my #AskAFuturist thread on Twitter with this question: "What have you been most wrong about in the past?"The short answer is that I got lots wrong, particularly in the early years when I was less cautious about making actual predictions (this is a surprisingly small amount of the work of a futurist). But having analysed why I was wrong, there is an incredibly consistent theme. I don't think I have been very wrong (if at all) about *what* is going to happen. But I was consistently wrong about *when* it would happen. And always in the same direction. I was too positive, or optimistic.It took me a few years as a full time futurist to learn this lesson, and it was part of the thinking that went into High Frequency Change. There are many factors that get in the way of possibility becoming reality.But you don't care about theory do you? You want to know when I was wrong! OK. Let's dive in to some examples.

Wearables? Ahead of their time

For the first two or three years I was working full time as a futurist, I was consistently underestimating the time it would take for technological possibilities to become everyday realities.Take this example from an interview I did with CNBC back in 2014. Here, I was rather forward in predicting the uptake of wearables. Sure, the smartwatch has been something of a success (Apple alone now sells more watches than the entire Swiss watch industry), but wearables are not yet truly ubiquitous. And the smart glasses I could see coming back then are probably still five years away.Do I still believe that we will start to use other devices as our primary digital interface? Absolutely. A small cloud of connected devices can provide a much lower friction interface to our digital world if their interface is truly intuitive. But right now, the experience still isn't that slick, even with the Apple Watch. And charging it remains a bit of a commitment.We'll adopt more wearable tech when its use is just natural. Take the smart shoe inserts I reviewed a few years ago that connect to your navigation app in your phone and tell you when to turn left or right without looking at your screen (themselves worthy of a retrospective blog post at some point). At some point I think we will have more tech like this that takes advantage of our other senses, other than sight and sound, to subtly feed us information. But such devices being so ubiquitous as to be a normal part of your everyday trainers? That's still some time away.

A smarter office? Not yet

How about this interview I did with CNN, also in 2014, about the future office. Here, I am incredibly optimistic about the timeline for some technologies: eye-controlled cursors, smart glasses, and VR video conferencing. All of those are here of course. They were here in some form in 2014 when I did the interview! I had (and must get back from the person I lent it to), a USB eye-tracking interface from a company called The Eye Tribe, that was already pretty slick. But slick enough to replace (or augment) the mouse or touchscreen? Not quite yet. But I think we'll get there, even if it is just part of the smart glasses that I still think are coming - eventually.Hey, at least I was sceptical about implanted microchips...

3D printing

I've written in the past about one of my most optimistic moments about the pace of change: my conviction that a lot more stuff will be 3D printed. This seems to make so much sense rather than manufacturing for an uncertain market on the other side of the world and shipping finished goods at great expense - both financial and environmental. If we can manufacture on demand, then we should. You can read the full article here. TLDR: there are many barriers but eventually additive manufacturing becomes a lot more mainstream in (the alternative to) mass production.

The end of Facebook

Perhaps the timeline I have got most wrong is around the decline of Facebook. Based on this post I was already predicting its decline back in 2011! The gradient of that decline has been a lot shallower than I expected. It continued gathering users in new markets even as it lost them in others, and it made the transition to mobile better than expected. Still, one day it will be eclipsed - not necessarily as a company, but as a network.

Back to the theory

The lesson I learned from all this, is that it's not enough for things to be possible, or even highly desirable for the relevant audiences, in order for them to happen. There are many social, cultural, legal, financial, and behavioural barriers to change. These are much harder to predict or even understand than the primary drivers of scientific possibility and objective benefit. Or in short, it's much easier to predict what will happen than when it will happen. These days I am much more cautious about the pace at which things change. Hence, in High Frequency Change I tried to analyse some of the factors that inspire and delay change, making that more nuanced argument about what moves fast and what doesn't.What is important when developing strategy though, is the possibility of high frequency change. As the current crisis has shown, there is enormous value in preparing for accelerated change rather than optimising completely for your current environment. This is a theme I return to in my next book, Future-Proof Your Business. Watch this space...

#AskAFuturist: Will we ever have flying cars?

Will we ever be able to zoom through the skies in our own flying car like George Jetson? Not any time soon, but there are flying taxi services coming.

Will we ever have flying cars? This #AskAFuturist question came from Danny Seabrook (@Danny_Seabrook) on Twitter, where he asked more specifically: "Are we going to be driving around like the Jetsons any time soon?"To answer this I have collected and edited together some of my previous posts on flying cars into one single guide. But I'm afraid answering this question has to start with a question: what do you mean by a flying car?

Flying car-toons

The Jetsons was a cartoon that ran initially for just a single season in 1962/63. That its influence is still felt is testament to the quality of the shows writing and design, but perhaps as much to the impact (and frequency) of re-runs. The show tells the comic stories of a family living their lives in 2062 - basically The Flintstones but set in the future. Their home, equipped with all kinds of crazy gadgets, is on stilts above the clouds. They travel around in a flying car with a big glass bubble on top. What technology this car uses for levitation and propulsion is unclear, since it has no wings and just one or two antenna-type devices that appear to release some form of exhaust.By ‘driving around like the Jetsons’, I take it to mean that Danny’s asking whether we will have flying cars. And by ‘soon’, I’m going to say Danny means the next five years. I could ask Danny, since he’s not just some random on Twitter but basically family. But these are the questions I want to answer, so I’m just going to crack on.So, what do we mean by a flying car? Is it something like the Jetsons' own vehicle? By that I mean something that a) levitates off the ground without any obvious wings, and b) anyone can get in and fly. Or can we be a little more flexible about the definition?

Powering the flying car

There are two clear problems with the Jetsons' style flying car: power, and people.As I note above, it is unclear how the Jetsons' car flies. Somehow, with very little obvious equipment, it overcomes the pull of gravity and is propelled through the air. Given that we don't yet truly understand the mechanism by which gravity interacts with our world, let alone have developed a way to counteract it, this seems far fetched. Even if we do discover and implement a means of countering gravity in the next five years, I'm going to suggest it might be quite energy-intensive. In other words, squeezing it into a passenger vehicle might be tricky. And all this before we have even thought about how the car might move forward and perhaps more importantly, steer and stop.

Do you trust other drivers with a flying car?

The even greater issue though is the people component. George Jetson is permitted to have pretty much free reign of the skies in his little flying automobile. While I'd argue about half the people on the road shouldn't be trusted with anything more powerful than a pedal-powered go-kart. Given the absolute havoc we can wreak with four wheels, do we really want to give people the power to drop in through our roofs when they screw up? I think not.So, if we are going to have flying cars soon, they have to be powered in some more conventional fashion, and either flown by trained and regulated pilots, or by similarly controlled machines.

Uber Elevate

Back in 2018 I spoke to James Max on TalkRadio about Uber’s latest announcements on self-flying drone taxis. At its second Elevate summit, the company announced partnerships with NASA and five aerospace companies to design, build, and test such vehicles, as well as showing some mock-ups of what they could look like.The idea was, and remains, to scale up a toy drone to the point where it can comfortably seat a couple of passengers and fly them around in safety and comfort. At the time I said that the technology looked to be about a decade out. It looks like I was out by about 50%.

Flying cars: tech and regulation

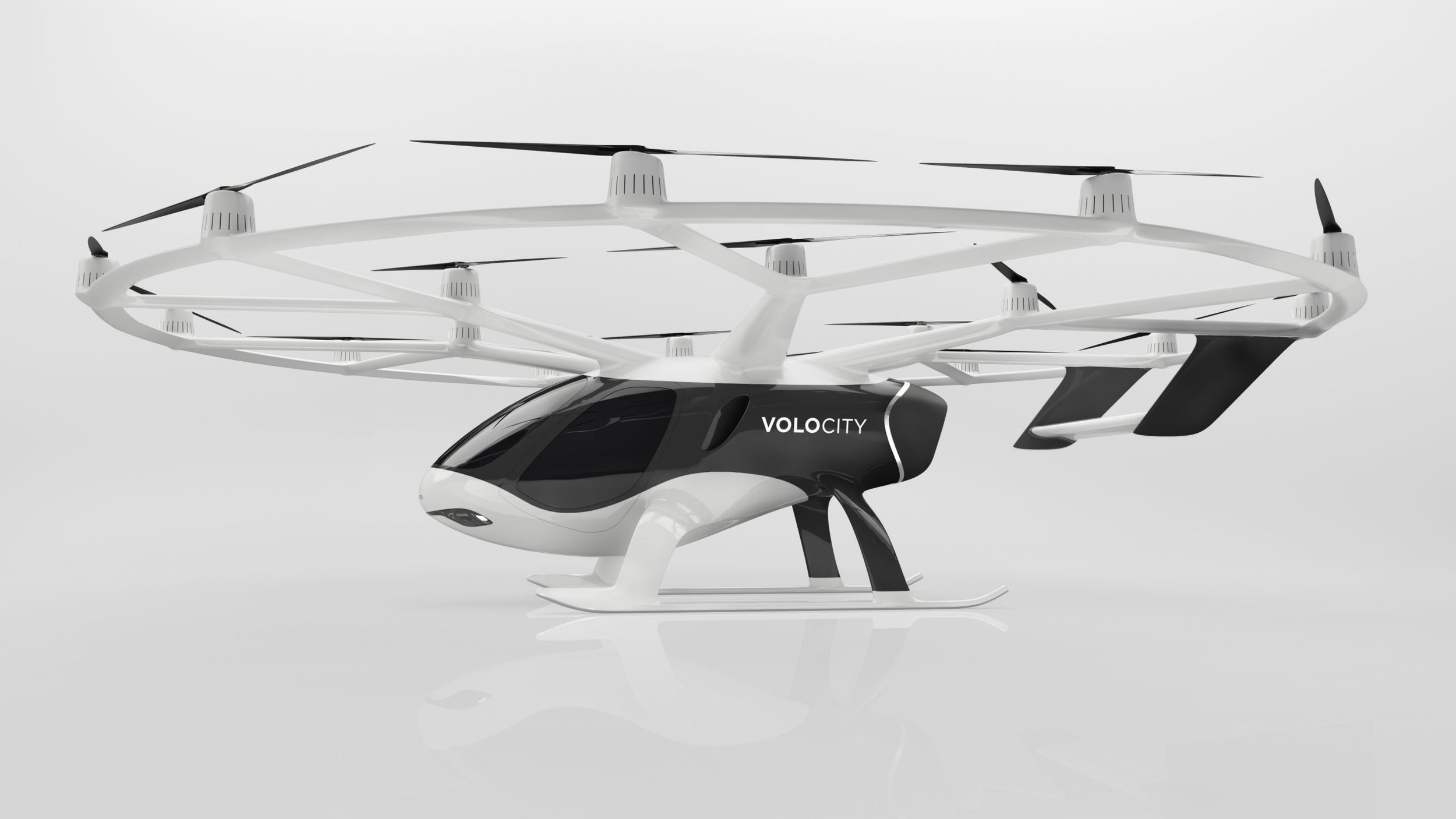

In 2018, the tech just wasn’t ready: it needed better batteries, lighter materials, quieter rotors, new safety systems, more reliable object detection and more. And likewise, we were not ready: the regulations surrounding self-flying are many and complex, we don’t yet have confidence in robot pilots, and we haven’t even started thinking practically about what these devices might mean for our lives and work.Fast forward a couple of years and a lot has been achieved. Most of the technological challenges, at least from a mechanical and electrical point of view, have been overcome. The fully autonomous robot pilots aren't quite there yet, but a number of companies, including Uber and Volocopter, are close to being able to enter service around the world in the next two to three years.Note, though, that these are not taxis that you will be able to hail from any street corner or rooftop. The flying taxi isn’t a straight replacement for its wheeled alternative. Door-to-door flying is impractical in built-up areas. More likely these vehicles would have to land on a nearby pad. Yes, there may be many more of these than there are airports — eventually — but you’re still going to need last mile transit from the pad.

Point to point

Where is it for then? I can see a business case for these devices doing short suburban or intercity hops. Uber is aiming for a range of 60 miles with a five minute recharge time. In the UK that might be a quick trip from Manchester to Liverpool or Leeds, around larger cities like London, or from London to Brighton. The speed of this travel might make it an attractive alternative to rail or road, particularly for business travel, and when a self-driving car can complete the trip.In places like the US, with giant sprawling conurbations like LA or the Tri-State area, this form of transport really comes into its own. Rapid connections between business districts might be enormously valuable there.But this isn't going to be mass transit. This form of flying car does not replace road travel or more importantly, trains and buses. This is high speed, high convenience, luxury transport for the time being at least.

Like the Jetsons?

So, will we be flying around like the Jetsons any time soon? Sorry Danny, that's a hard 'no'. We don't know how to make vehicles like that fly, and even if we did, I wouldn't trust most people to fly one.Self-flying taxis in the form of up-scaled drones are absolutely practical in a defined set of scenarios. You will be able to ride in one by 2023 I suspect - maybe sooner. But they won’t be replacing your commute any time soon.

#AskAFuturist: What is the future of the high street?

What is the future of the high street? The first step to building tomorrow's high street is accepting that the one we know is dead and gone.

What is the future of the high street? This question was asked on my #askafuturist thread on Twitter but also raised by an optometrist at the Stockport Business Summit at which I spoke yesterday. So, I figured now would be a good time to tackle it.The original question from Jasper Hegarty-Ditton was this: “With the recent news around retail decline in 2019 and everyone predicting its continuation, what are more innovative ways we could use our city centres? (Rather than just filling with bars/restaurants/coffee shops).”

Real, structural decline

The first point to make is that the decline of retail on the high street is both a) real and b) structural rather than cyclical.To put the decline in numbers, we lost almost 2500 shops in 2018. Twice as many shops closed as opened. This left us with a vacancy rate of over 10% by the middle of 2019. On top of this, it is estimated that the top 150 retailers have on average around 20% too much space – more than they can afford.This translates directly into job losses. Over 140,000 jobs in retail disappeared in 2019 and that is an ongoing trend, not a one-off.So, why the decline?

Shops are not coming back

When I say the decline is ‘structural’, I mean that bricks and mortar retail is not going to make a comeback any time soon. When you understand why retail has declined, and how disconnected it is to the overall state of the economy, you can see why. That’s not to say that there won’t be a bounce when the economy booms, but it will never reach the same levels as before.Almost 20% of our spend has shifted online. This combined with the smaller number of shops means there is less reason to head to the town centre, compounding the effect and reducing the chance of serendipitous discoveries and knock-on expenditure. Footfall is falling year on year.More of our expenditure will shift online as we outsource more of it to automation. I genuinely believe that within a decade or maximum two, we won’t shop manually for more than half our weekly goods. A smart digital assistant will know what we want, order it, and ensure it is delivered. For some people that will be food and sundries. For people like me, that might even include clothes (I buy the same items over and over again as they wear out).

Future of the high street: less stuff to sell and buy

Note that online retailers are struggling as well. But this is mostly about competition, the economy, and some fundamental issues with the costs of logistics and particularly returns. These things can be resolved.What can’t be resolved is the simple reduction in the volume of things we might shop for. Digitisation is destroying, or has destroyed, the market for many of the staples of the high street. Physical media is largely over, apart from the boutiques and back streets and high value luxury items. It is not coming back outside of those niches. That means we can support a fraction of the number of shops selling books, music, film, stationery, photo processing etc.Technological convergence means we also don’t need as many devices on which to consume all this media. Digitisation of media doesn’t just disrupt the distribution businesses; it disrupts the device manufacturers. One device can now act as your radio, TV, music player, camera, remote control, games console and much more.There will undoubtedly be new classes of device in the future. But it’s hard to see how these devices break out of this digital media paradigm in a way that requires anything more than a showcase presence on the high street.

Distributed manufacturing

As we look to the future, the situation gets even more stark. It is taking a lot longer than expected, but you can foresee a time when many other products succumb to the same digitalisation. Clothes for example: why ship volumes across the world when you can manufacture on demand close to the customer? Lower cost, lower carbon footprint, less waste. Are those clothes likely to be fabricated at home? Not any time soon. But one smart fabrication unit could replicate many different designs shared digitally. With the ability to try on clothes in full photo-realistic fashion in mixed reality, there is even less need for physical products in a high street store.So, in smaller towns and cities, the loss of the high street is pretty much assured – at least as a venue for retail. As I said on Jon Richardson’s show, Ultimate Worrier: the question is not whether the high street is dying. It’s “What do we do with the corpse?”

The high street is dead. Long live the high street

So, is there hope for the future high street? Absolutely. But if it’s not in shopping, what is it? It is in living, working, learning, and socialising. Well, and a bit of shopping.As I said, larger city centres will remain destinations for shoppers with large, experience-focused brand stores continuing to draw crowds. The shops that survive on smaller high streets will be ones that offer high levels of service and craft, as well as products or services that are more spontaneous purchases.The more that our world is driven by mass market, low friction services, the more I believe we will crave the unique, the original, and the personal. Having a human-fronted service, whether that is an optometrist, or a butcher, will be an everyday luxury that I think will many will crave and choose as a badge of their personal brand. And a statement about their wealth and status.

Reassuringly expensive

For these businesses to survive, they will have to be relatively highly priced, when compared to their highly digitised low-friction alternatives, because what they offer will by definition be low volume. That can be a scary prospect for the business owner. But the evidence is that the people who can afford to will patronise such businesses if the service they offer matches the pricing.There is a ceiling to the prices they can charge though, and if these business are to become a viable part of a diverse high street mix then we will need to see reform on business rates and rents.

Spontaneous shopping

Even when we get much of our groceries online and delivered automatically, there will still be those occasions where we just need to grab an extra pint of milk, a bottle of wine, or a bunch of flowers at short notice. Metro grocery stores that cater for these needs are probably here to stay.Both the more craft based businesses, and the metro grocery stores will rely on footfall to survive. Almost no retail business can survive if it is surrounded by empty units without traffic. If other shops won’t drive that, what will?The critical strength of the future high street is in diversity. It is not just a place to shop but a place to live and work, learn and play, eat and drink. It needs to be a place for everyone, particularly all ages.

A future high street for everyone

As I’ve written about before, some towns and companies are already making interesting moves in this direction, with Legal and General investing in bringing retirement living into city centres to replace failing retail space. They are not only building homes but amenities such as doctors’ surgeries, creating a gravitic pull for a wider range of potential city-centre tenants. This is likely to increase the appeal of city centre living to, for example, families with young children. That might in turn drive the construction of more schools and nurseries in city centres.With the shift to electric and ultimately self-driving cars, and even better, drives towards walking, cycling and public transport, town centres can become cleaner, safer places. Many councils, such as Stockport, are now building new, green spaces in the middle of cities.I picture a future high street that is a rich blend of places to live, work, play, eat and drink, study and shop, alongside services for health and beauty. Clearly some of those components are there today but it is the others we need to bring in, and fast if we are to halt the decline of many high streets and save the businesses that still populate them. That will require intervention by both central and local government, and great innovation and flexibility on behalf of landlords, many of whom may not be financially incentivised to do so. Accepting lower rents on their properties to keep streets vibrant may well lead to a devaluation of their asset, something that could be much more difficult for them than having empty units. Changing that situation may too require government intervention.

#AskAFuturist: The future of privacy

In response to my #AskAFuturist request, Franck Nijhof asked about the future of privacy. What will be left of our privacy in 50 years?

“But for real, the future of privacy, what will be left of it in 50 years...”This question came from Franck Nijhof, also known as @frenck, one of the most prolific contributors to my favourite open source project, Home Assistant.To answer it, we must start with some questions. What do we mean by privacy? What are we keeping private? And from whom?

All or nothing

There are two opposing schools of thought here:

- “None of your business” - One school of thought says that everything should be private unless you explicitly choose to share it. That no-one should have the right to compel you to share it, without at the very least, compelling evidence of wrongdoing.

- “What have you got to hide?” - The other school of thought asks, “what have you got to hide?” It suggests everything should be out in the open and only terrorists and deviants keep things concealed.

Most of us inhabit the grey area in the middle. We’re happy to share some things, we share others grudgingly. Sometimes we make informed choices about trading some privacy for services, such as social networks. Most of the time we make such choices based on very poor information and understanding.The short answer to “what is the future of privacy”, is more of the same: we will continue to muddle through making mostly OK choices based on limited information about what we should share. Our privacy will be alternately infringed and reinforced by governments, regulators and private corporations alike.The bigger answer requires addressing some of the specific technologies, business models, and pressure points that will affect the future of privacy. The answers it reveals might show up the cracks between different jurisdictions.

Future of privacy: the long answer

Let’s divide the challenge between public and private, asking two questions:

- Will corporations continue to gather data about us in a bid to target us more accurately with advertising and change our buying (or voting) behaviour?

- Will governments make increasing use of technologies like facial recognition, infringing our privacy under the cover of making us safer?

Corporate data gathering

A few years ago, I had conversation with the chief data scientist of what was then Demandware, now Salesforce Commerce Cloud, Rama Ramakrishnan. Rama is now Professor of the Practice, Data Science and Applied Machine Learning at MIT Sloan. What he told me rather exploded my understanding of the drivers for social networks and search engines gathering big data about us.“When it comes to understanding shoppers, the key lesson is that you are what you buy. That I am of Indian origin and live in a particular suburb of Boston is not particularly valuable. The fact that I like a certain brand of boots, that is interesting.”What he means, and what he went on to explain in the paper that I wrote for Demandware on data-driven retail (sadly no longer available), is that much of the information we are worried about sharing, and that the social networks appear to have prized collecting, is actually of very little value when it comes to selling advertising or targeting us. Put another way, we give so many explicit signals about what we want that there is little return on investment on spending billions trying to infer what we might want from other data about us.

The value of data

I see lots of companies starting to get to grips with this fact. They are starting to understand that, even before any regulation, or consideration of the security risks it presents, the cost of gathering and processing lots of personal data about us is often not outweighed by its value. Better just to have the 10% of – often at least semi-anonymous – data that gives 90% of the value.Now, there is still lots of deeply personal and perhaps compromising information in our clickstreams. We are right to be cautious about what happens to that information. Here, regulators have a role to play, looking both at what is collected, how it is stored, and how it is used. But the diminution of the business case for large-scale data hoarding gives me hope that this sector can be regulated. If the value of our most deeply personal data proved to be much higher, I would worry that business would lobby and wrangle to minimise oversight.This is the same reason why I’m not *that* concerned about the data gathered by voice assistants like Alexa. Yes, they are picking up more than our explicit commands. But storing and processing that morass of data probably has very little value. I’ve still chosen to keep voice assistants out of shared areas in the home until my kids are old enough to make a conscious decision about sharing their own voice data. And they can always be hacked, but that’s a different story…

Data ownership

Of course, our data does still have value. “So why don’t we see that value?”, many ask. Many people have proposed putting personal data into the hands of individuals rather than corporate behemoths. There are even proposals to ascribe it some sort of property rights, making it a tradeable commodity. It’s an idea that I have discussed on this blog before. I still believe that in the future we will store most of our personal data inside a firewalled cloud account and release it only on a case by case basis when we see value in return. Sometimes that value might be financial – such as when it is a signal of a willingness to buy. In this case there are already mechanisms to monetise that signal, through cashback services like Quidco. But sometimes that sharing might be more community minded – such as with the sharing of health data for government information or large-scale studies.

Is it worth it?

It’s unlikely that we will make the decision to share ourselves for reasons of practicality, and of value. Practicality because the number of requests per day will likely be overwhelming. We will give our personal AI assistant a set of broad rules and it will take decisions based on those rules, feeding us the exceptions and learning from each one. Value because, unless it is a very explicit buying intention, our data just isn’t worth very much!As Chloe Grutchfield of adtech specialist RedBud Partners pointed out on a panel I was part of in late 2019, most people would stand to make a maximum of 50p per day from their data. That would be based on them signing up for multiple data-driven reward schemes and sharing their data without much thought for their privacy. Now, that might be enough to subsidise the cost of the personal AI making the data-sharing choices for you, but it won’t do much more than that. You can’t make a living from your personal data.So, will corporations continue to gather data about us in a bid to target us more accurately with advertising and change our buying (or voting) behaviour? Yes. But I think they will be increasingly selective about what they gather, and more conscious about how they store and use it. In the long run, we will likely have more granular control over what is collected and shared. And we will reap some of the (small) reward from it. Here, the future of privacy is surprisingly positive.

Government grabbing data

I am more concerned about the overreach of government when it comes to the future of privacy, particularly in places like the UK and US. Here, there is limited experience of authoritarian states and the speed at which the tide can turn against different groups. The “what have you got to hide” lobby is very strong, particularly in the UK where there is less of a counterculture of those completely opposed to federal government. That doesn’t mean that I respect those groups – they rather terrify me. But they are nonetheless something of a balance to governmental overreach.The ruling in the UK on the use of Live Facial Recognition by the South Wales Police sets a precedent, albeit one based on a limited version of the technology. These are not the networked cameras scanning the streets and monitoring everyone’s movements that you might see in a dystopian scifi. Rather these are mobile units running against a bespoke set of target individuals at each location they are deployed. That said, the fining of a man who covered his face to avoid the system on trial in Romford sets a worrying precedent of its own.It only takes an authoritarian home secretary (ahem), and a terror incident to see the scope of such technology expanded. And with us outside the European Union and challenges to judiciary oversight, I am concerned how fast this might happen.

Beyond cameras

That concern extends beyond cameras. Our legislature in the UK has been using technology as a scapegoat for all sorts of societal ills for a few years now. It is very happy to discuss draconian measures to lock down access and monitor people’s use. The “what have you got to hide?” lobby might do well to read a history book or two and see just how many groups fall into the government’s sights when things start to slide.Will governments make increasing use of technologies like facial recognition, infringing our privacy under the cover of making us safer? Yes, in the UK, US and probably places like Australia, they almost certainly will. In the EU, with different attitudes and stronger regulators, the risk feels much more distant.

Future of privacy: What will be left in 50 years?

The answer to this first question then probably comes down to where you live. We won’t have global harmonisation on laws for many more than 50 years. In the meantime, I think you will see the boundaries of your privacy expand in both the public and private domains if you live in Europe. Good news for you Franck. Elsewhere, the future of privacy is perhaps not so rosy.

#AskAFuturist: When will we see the end of cash?

"What year doth dosh disappear forever?" This was the precise question asked on Twitter by Sandy Lindsay MBE. Here's my answer.

"What year doth dosh disappear forever?" This was the precise question asked by Sandy Lindsay MBE on Twitter in response to my call for questions to #AskAFuturist. So, when will we see the end of cash? Or will we always keep a little wonga in our pockets?The decline of cash as a form of payment has been precipitous. At the end of the 2000s, cash still represented around 60% of all payments made. By the end of the 2010s it was down to around 40%. The Access to Cash Review run by former financial ombudsman Natalie Ceeney suggested that at the current rate of decline, cash use would end as soon as 2026.This is unlikely. As the report notes, the people making the shift from cash to card today are those who can. Those with the financial stability, confidence in technology, and access to banking to do so. This represents maybe 80% of the population, so cash use will continue its steep decline. But moving to cards is either impractical or impossible for the last 20% or so. For a variety of reasons - poverty, disability, financial insecurity - this group can't or won't access digital banking.Eventually most of these people will make the switch, supported through a combination of education, better infrastructure (e.g. the last remaining all cash shops taking cards or ending their excess charges and minimum payment limits), and new services designed specifically to support them. But the rate of decline of cash will naturally slow down as we reach the point where more work is required to help people to transition.

End of cash: Difficult transition

The transition away from cash won't be smooth or clean. As we use less and less cash, so there is less reason for shops and banks to support it. Bank branches and cash points are closing. More and more shops and cafes are card only, having recognised the real costs of handling cash. Those people who don't have access to alternatives are increasingly marginalised. Eventually the banks are likely to be allowed to co-operate to maintain some form of basic service while cash usage drops to just a few percent of transactions.But I don't believe it will go away altogether. Back in 2011 when trialling a watch with integrated contactless payment technology, I questioned whether I would still be carrying coins in my pocket in five years. I was right. It has been a few years since I have regularly carried cash, except for maybe a single note for emergencies.Cash will remain, albeit in limited usage and in very small volumes, for the foreseeable future. It has too much power as a token, or an icon, for it to be eliminated altogether. My prediction is that we get down to 20% of transactions by the middle of this decade, and down to maybe 5% by the middle of the next. But there or thereabouts cash remains for at least a couple of decades after that.

#AskAFuturist: Will we ever have driverless cars?

Answering a sceptic on Twitter as part of my #AskAFuturist series, I explain whether we will ever have driverless cars, and why he's right to be sceptical

Will we ever have driverless cars? In my #AskAFuturist thread on Twitter, Ian (@ianeditz) asked a rather more negative version of this question: "Why will we never have driverless cars?" Ian is a sceptic when it comes to the idea of autonomous vehicles. In this post I will explain why he is right to be sceptical, but ultimately why cars will indeed drive themselves.

The case for scepticism

A truly driverless car, or autonomous vehicle, must be able to pilot itself in all conditions, with or without passengers. This means every street scenario, from a four-lane highway to the narrowest and busiest city street. And it means every weather situation, from three feet of snow to the glaring sunlight on a mid-summer's morning. If you think this is simple, then you underestimate the incredible capabilities of the human brain, body and senses. We are unbelievably good information processors. We filter huge numbers of signals from the noise around us and react constantly with small adjustments to our speed, road position and more. Replicating and even beating human capability in controlled road conditions is within the bounds of current technological capability. But doing so in a range of conditions to which humans so readily adapt, is much, much harder.So, before we can have truly driverless cars there is first of all a technological challenge to overcome. Can we equip the vehicles with an array of sensors, and a digital brain to process their output, that is better than humans?

Better than human

The key word in that last sentence is 'better'. Autonomous vehicles don't just have to be safer than humans, they have to be much safer. Perhaps an order of magnitude safer or even more. Because from their inception they are fighting a very natural fear in us: the fear of giving up control. It is scary to consider being in a vehicle that can move at life-threatening speeds and that is constantly making decisions about your safety and other people's around you. Every time an autonomous vehicle fails and someone is injured or killed, the date by which most people will accept riding in an AV is pushed back. And sadly, this will happen many more times.This is before we even get into the issues of security. What's scarier than being in a rogue driverless car? Being in one that someone has deliberately hacked to cause harm. Right now car manufacturers are some way behind the curve on internet security. Lots of vehicles have shown themselves to be highly hackable. In fact the very nature of current vehicle electronics, using lots of components, both critical (e.g. the throttle) and non-critical (the stereo) interconnected over a relatively simple networking system, opens itself up to hacking.

Red tape

Because of the incredible risk to life that autonomous vehicles represent, they will naturally be covered by extensive legislation. This will take a lot of time, as legislation does, however much ministers might like to announce programmes of support for the technology and the companies building the cars.The legislation will undoubtedly require insurance cover that is somewhat different to what is required today. That too will take time for the insurance industry to organise. But who buys that insurance? Is it the owner of the vehicle? If so, what grounds do they have to be confident in the algorithms doing the piloting? So, is it the manufacturer of the car? Chances are that they may have bought in all or part of the software running the system, as well as most of the components that make up the sensors and systems on which it runs. So we have a complex chain of liabilities. This is true today, it just gets more complex when a human isn't in charge of the vehicle.It gets even more complex when you look at the trends in car ownership that are likely to be accelerated by autonomous vehicles. In short, most of us are likely to slowly move to greater reliance on fleet services like Uber rather than car ownership, especially in large cities. Car ownership seems to be losing prestige amongst young people who are learning to drive later and later. They are choosing to spend their money more on things to do than things to own (the subject of a future #AskAFuturist post). If a car can be at your door in minutes whenever you need it, and you don't get to drive it anyway, why own one?

The case for the defence

Given all of these good reasons to be sceptical, you might rightly ask why I am so confident that we will - eventually - have self-driving cars. This comes down to four things: culture, cash, safety and good old-fashioned human laziness.

Culture: do we even want cars anymore?

What I mean by culture is that we care less about cars now than we did a generation ago. They aren't the status symbol they once were. And in the context of a changing climate, owning a car - particularly a fast or extravagant one - is looking more and more like an unnecessary luxury, even an insult to your neighbours. I'm still a bit of a car nut but I recognise that fewer and fewer people share my passion. Self-driving cars allow us to get away from car ownership without requiring the large scale investment in public transport, cycling infrastructure, and city redesign that I would love to see, but do not see coming any time soon.

Cash: human drivers are expensive

The second point is more about the wider economy than cash in your pocket, though a subscription to a fleet service could be much cheaper than car ownership. Especially with economies of scale if most people go down that route. Human drivers cause accidents and traffic jams, which cost the economy and the tax payer an awful lot of money. I believe it is inevitable that self-driving cars will eventually be a lot safer than human drivers, saving us all a lot of money - and time.

Safety: computers don't get distracted

That leads neatly to the third point: safety. Of course the greatest cost of failures by human drivers is not financial but the cost of lives, blighted and ended. Self driving cars will be, statistically, a minimum of ten times safer than humans. Probably at least 100 times safer. The lobbying power that will be brought to bear by road safety campaigners once a direct comparison is possible will be hard to resist.

Laziness: we like low-friction lives

Finally, there is good old fashioned human laziness. We have strived for a few million years to apply technology to take friction out of our lives. And what could be more appealing than a service that whisks you from one destination to another with barely any interaction required? Ultimately I think this leads us to overcome our fear.

So, will we ever have driverless cars?

Yes. But, it's going to take a long time for all the reasons that Ian is right to be sceptical. Longer than people think. I don't think the technology will truly be there for a 'Class 5' self-driving car that can operate in all environments and conditions until the end of this decade, and I think it will take a few years after that for all the legal and legislative wrinkles to be ironed out. Along the way, sadly, I'm sure more people will be killed by autonomous vehicles that aren't quite there yet. There will be a public backlash against them. But ultimately, we will accept driverless cars because they make us richer and safer, and allow us to be lazier.##(A reminder at this point is worthwhile, that this is not what I want to be true but rather what I see happening. I can think of better alternatives but that's not the question I'm trying to answer).