Future Cities

Future cities are more than just ‘machines for living in’. They are the vehicle for cultural change, environmental rescue and the reinvention of our economy. Or at least, they could be....

Working with architects, developers, property companies, engineers, surveyors, law firms, local authorities, and sector bodies over the last few years I have addressed almost every aspect of our evolving cities: smart city technologies, future transport, energy evolution, changing patterns of work and living, retail, welfare, even the design and development process for buildings and infrastructure.

Collected on this page is a variety of my work on future cities, including conference talks, blog posts, and reports. If you are looking for a speaker, commentator, writer or consultant on future cities, then drop me a line via the contact form. Or just read on to find out more about how we will live and work in tomorrow's world.

“Would you like to work with NASA?”

What’s your dream client? The one organisation you would give anything to work with?

It will take me a little while to get over the moment that NASA called and said they were interested in my work on future cities. OK, that’s not quite how it happened. NASA’s Convergent Aeronautics Solutions programme is kind of an internal think tank at the organisation, created to tackle the problems that plague aviation around the world, across issues like safety and the environment. They work with an organisation called Shoshin Works to help them to facilitate external input into this mission. Shoshin Works called and asked me if I would be open to presenting my ideas on future cities to the think tank and taking questions, then following that up with a podcast version for public consumption.

I can’t share the original presentation with you, but you can listen to the podcast. And you can probably still hear my excitement.

Future Cities: Property and Construction

Tom Cheesewright talking about future cities in the closing keynote at the Property Week RESI conference in Cardiff, 2017

The property industry is inherently conservative. This is a sector that deals with assets that might last decades, so the people commissioning, designing, building and operating those assets need to be confident in its safety, utility, and return on investment. But in this age of high frequency change, the industry can be perhaps too conservative, missing opportunities to improve margins, cut waste, and improve the living experience of tenants in both the residential and commercial sectors.

Over the past few years I have spoken to a huge number of people in this sector, at conferences and via the media, to try to open their eyes to the possibilities presented by new technologies ('proptech'), and the threats to their business if they fail to adapt. With some of the traditional business models in this sector under clear threat, changing cultures of place and work, now is the time to think about tomorrow.

Working with top 50 law firm Freeths, I've engaged with the property, construction and proptech community, and fed back this insight through a series of events including roundtable discussions with Property Week.

Future Cities: Energy

The energy market is going through a period of rapid disruption, driven by changing demands, geopolitical instability, rising climate pressures, and broken economics. With many countries operating on ageing infrastructure and lacking the capacity or will for new public investment, this period of disruption looks set to continue.

The very nature of our energy system and economy is in flux, showing the stresses of many of the macro trends that I see touching every sector: the rising power and expectations of consumers, the expansion in very unfamiliar competition, and the shift in structure from centralised to networked.Understanding the future of energy is understanding the platform on which humanity continues to build.

Whether you are considering homes, industry, cities or transport, understanding the future sources of energy and the markets around them is critical. I’ve worked with many companies on the future of energy in different forms, including consulting in the UK and India. In 2017, I worked with global law firm CMS on an in-depth report on the future of energy, correctly predicting the UK's move away from domestic gas. You can download the report here.

Want to know what it's like to work with me to produce a report? Read the story of my project on the Future of Energy with CMS.

Planning the Future City

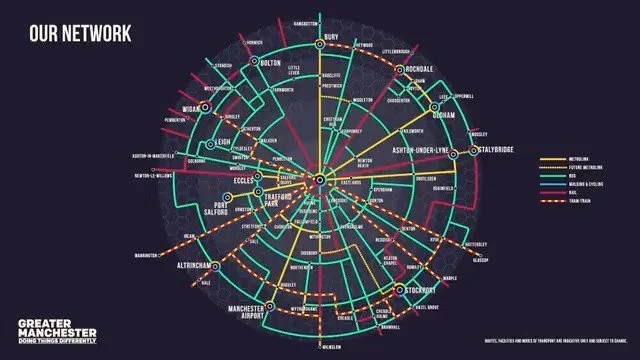

How do you plan tomorrow's city? I joined the steering group for the Manchester 2040 transport planning exercise, and working with economists and architects, helped to devise a bespoke version of the Scenario Planning framework that helped us to map the impacts of potential transport interventions on multiple future scenarios for the Greater Manchester region.

Today the output of that six-month project is being put into practice with massive transformation across Manchester's transport network. It's hugely rewarding to know I played a small role right at the start.

SMART CITIES

Smart cities is a bit of an uncool term now, with something of a backlash against the heavy push of new technologies. But however we feel about tech, tomorrow’s cities will have to be smarter.

For me, smart cities are about much more than technology. They are about creating spaces for people to thrive, in life and in business, and doing so in a way that minimises our negative impact on the environment.While I'm fascinated by the technology being deployed in smart city demonstrators like Santander, I'm also interested in working with local authorities on how they respond to the challenges of austerity, the ageing population, workforce automation, and the changing environment and economy.

Through consultancy project and short term engagements, I've helped local authorities to think about how they might restructure themselves for the future, refocusing around the citizen to deliver optimal services in an affordable manner, and remaining responsive to changing demands.

Future Cities: Transport

The shift to all-electric motive power, and the advance of artificial intelligence presents huge opportunities for autonomous vehicles. But while self-driving cars capture the headlines, they aren't the whole story when it comes to the future of transport.

Mass transit, cycling, walking, and new urban transport modes all have a big role in tomorrow's world. That's why I'm so excited to work with companies like Trainline and Stagecoach, and host events like the World Rail Festival in Amsterdam.

Get in touch

Interested in engaging me around a project on the future city? Get in touch via this form and someone will be back to you as soon as possible. Please provide as many details as you can about the project: is it speaking, writing, consulting or broadcasting - or maybe something else? What's your timescale?