news from the future

Future of Rail: Even foresight needs constraints

Sometimes foresight is about breaking constraints and forcing people to think beyond today. But sometimes we need to operate with constraints, to find what it fantastical but not implausible.

Replacing the car

If we are to tackle the challenges of the car, we need to replace the sense of freedom it offers, for rich and poor, individuals and families

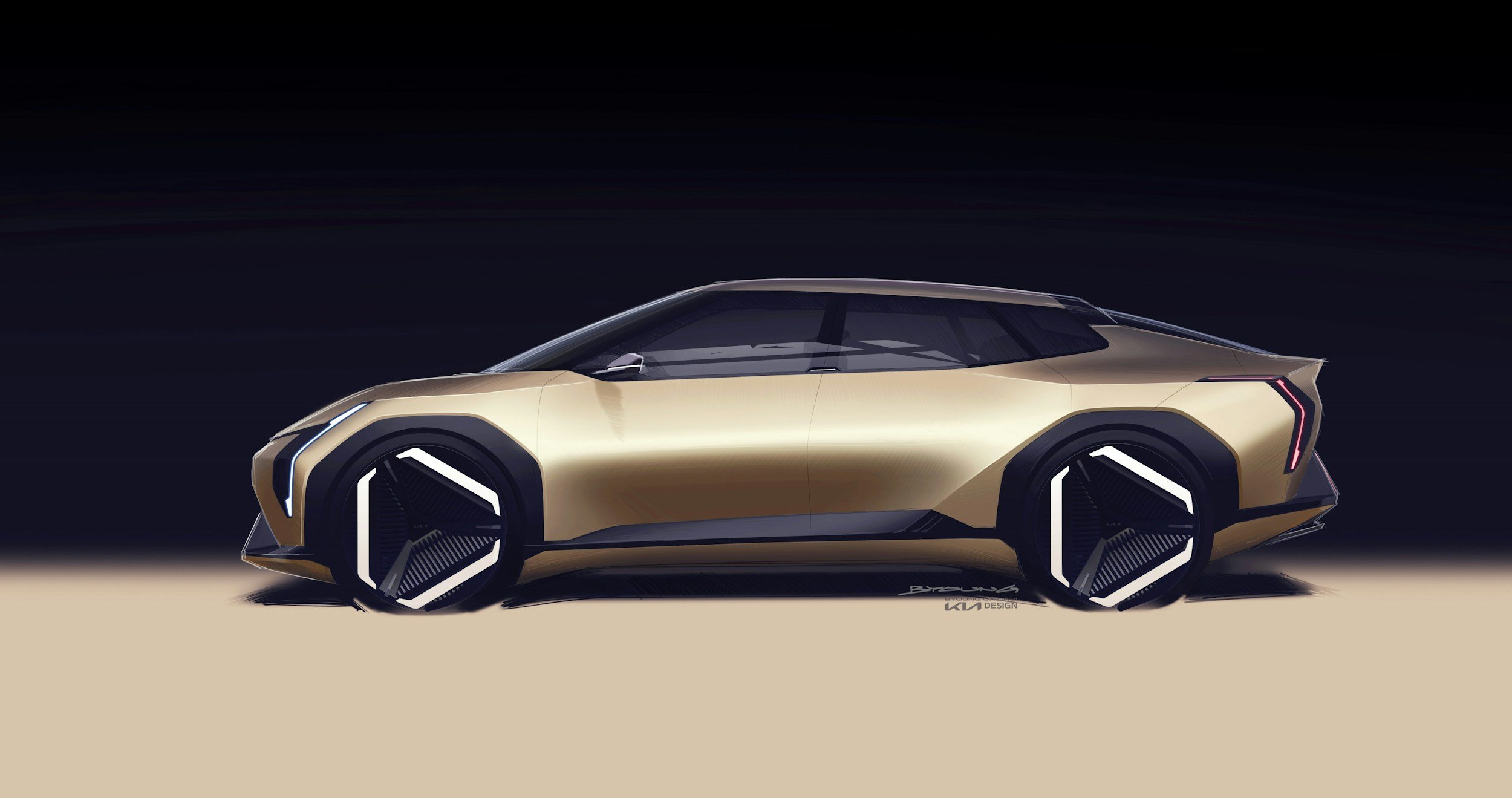

Your next new car might be a new brand, and a new shape

Your next new car might not look like your old one. And it might come from a brand you've never heard of. What will you be driving in the future?

#AskAFuturist: Will we ever have flying cars?

Will we ever be able to zoom through the skies in our own flying car like George Jetson? Not any time soon, but there are flying taxi services coming.

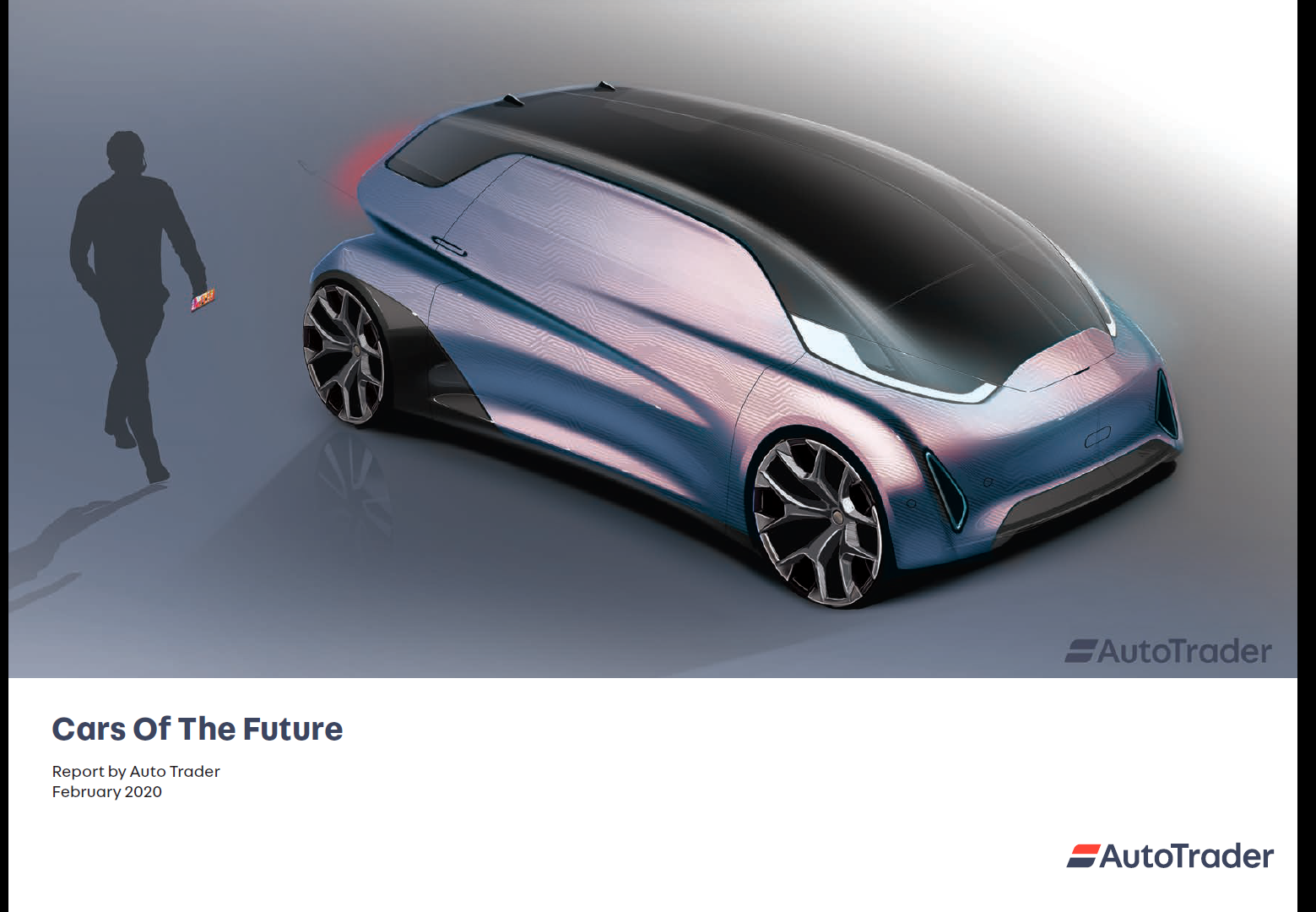

Report: Cars of the Future, with Autotrader

Today, we're releasing the report I've been working on with Autotrader on the car of the future.

Tomorrow's cars will reshape our cities

Cars shaped today's cities. Tomorrow's cars will reshape our cities, as we move to a world of autonomous electric vehicles.

- Future Car 4

- Future Communication 17

- Future Health 10

- Future Media 10

- Future Technology 16

- Future of Business 10

- Future of Cities 9

- Future of Education 7

- Future of Energy 8

- Future of Finance 19

- Future of Food 6

- Future of Housing 3

- Future of Humanity 22

- Future of Retail 9

- Future of Sport 1

- Future of Transport 9

- Future of Work 10

- Future society 11

- Futurism 20

- clippings 1

Archive Note

The archive of posts on this site has been somewhat condensed and edited, not always deliberately. This blog started all the way back in 2006 when working full time as a futurist was still a distant dream, and at one point numbered nearly 700 posts. There have been attempts to reduce replication, trim out some weaker posts, and tell more complete stories, but also some losses through multiple site moves - It has been hosted on Blogger, Wordpress, Medium, and now SquareSpace. The result is that dates and metadata on all the posts may not be accurate and many may be missing their original images.

You can search all of my posts through the search box, or click through some of the relevant categories. Purists can search my more complete archive here.