news from the future

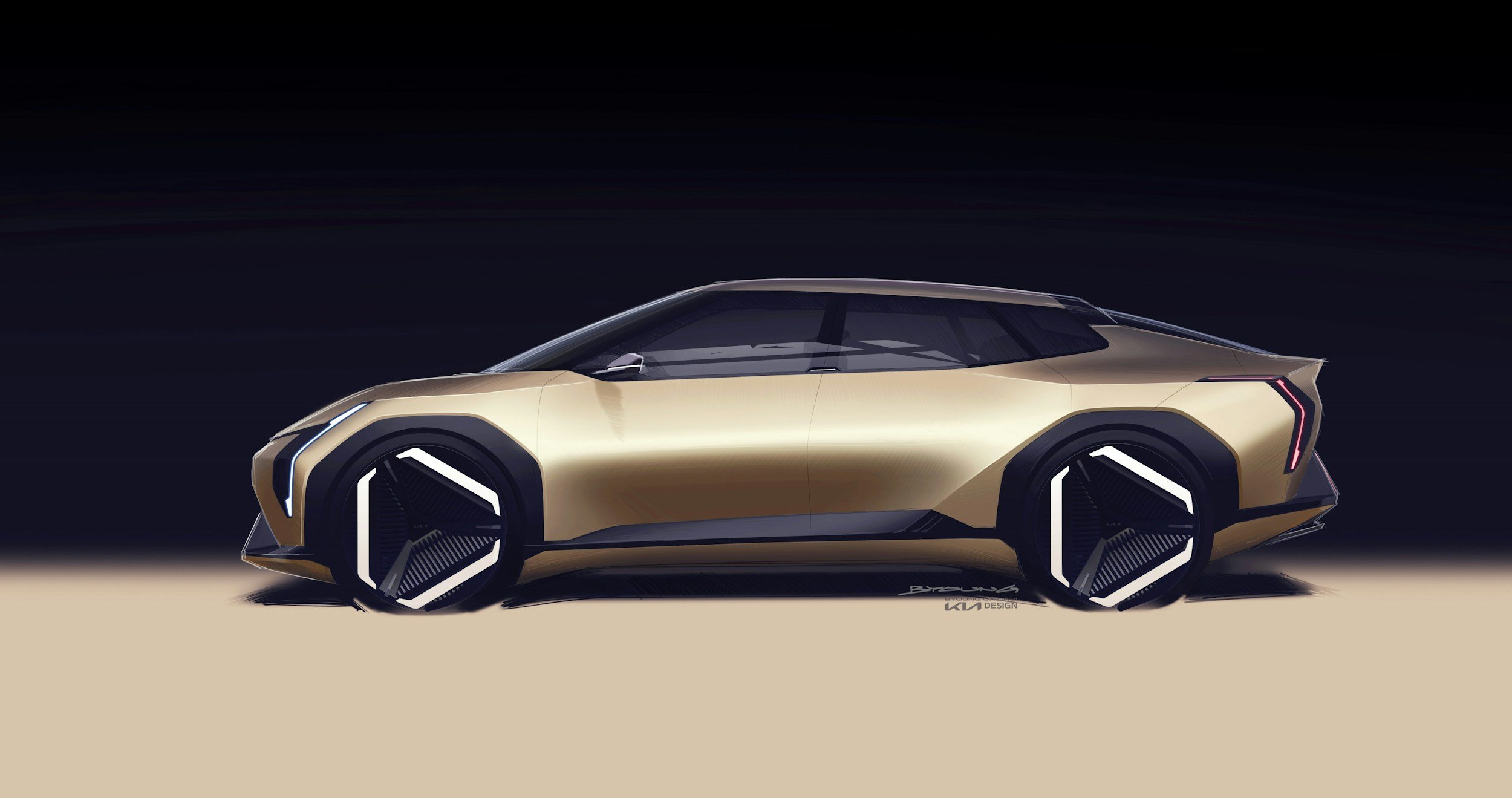

Replacing the car

If we are to tackle the challenges of the car, we need to replace the sense of freedom it offers, for rich and poor, individuals and families

A race between the four horsemen

Four horsemen of disaster are vying to define our next three decades. Which one lands its blows first will determine our future.

- Future Car 4

- Future Communication 17

- Future Health 10

- Future Media 10

- Future Technology 17

- Future of Business 10

- Future of Cities 9

- Future of Education 7

- Future of Energy 8

- Future of Finance 19

- Future of Food 6

- Future of Housing 3

- Future of Humanity 22

- Future of Retail 9

- Future of Sport 1

- Future of Transport 9

- Future of Work 13

- Future society 12

- Futurism 20

- clippings 1

Archive Note

The archive of posts on this site has been somewhat condensed and edited, not always deliberately. This blog started all the way back in 2006 when working full time as a futurist was still a distant dream, and at one point numbered nearly 700 posts. There have been attempts to reduce replication, trim out some weaker posts, and tell more complete stories, but also some losses through multiple site moves - It has been hosted on Blogger, Wordpress, Medium, and now SquareSpace. The result is that dates and metadata on all the posts may not be accurate and many may be missing their original images.

You can search all of my posts through the search box, or click through some of the relevant categories. Purists can search my more complete archive here.