news from the future

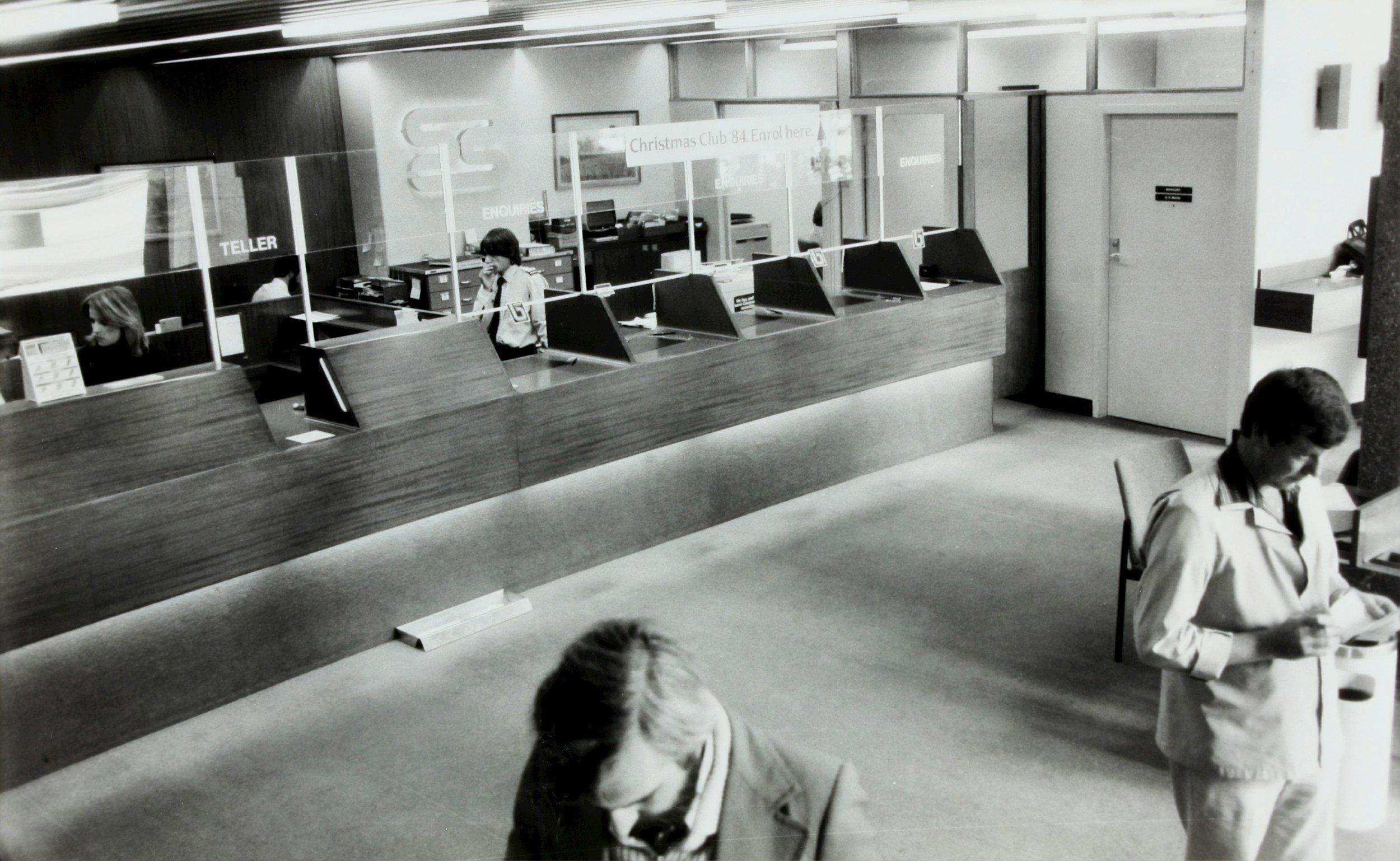

Cash isn’t dead (just yet)

After a quiet couple of weeks on the media front, I find myself back on BBC 5Live talking about the death of cash, following a discussion in parliament about legislation to ensure its continued support by retailers.

The future of consumer credit

Our attitudes to debt are changing, while technology eases our access to borrowing. What is the future of consumer credit in a low-friction world?

#AskAFuturist: When will we see the end of cash?

"What year doth dosh disappear forever?" This was the precise question asked on Twitter by Sandy Lindsay MBE. Here's my answer.

Building the Bionic Banker

When it comes to our banking interactions, there is good friction and there is bad friction. Eliminate the good friction and you risk customer loyalty.

Raging against the invisible machine

The Luddites smashed machines they could see that were taking their jobs. How will the new Luddites rage against invisible, ephemeral machines?

TSB: When tech is everything, failure is only human

Technology failures are almost always human failures when you examine the detail. Technology allows us to do more and shouldn't take the blame.

- Future Car 4

- Future Communication 17

- Future Health 10

- Future Media 10

- Future Technology 16

- Future of Business 10

- Future of Cities 9

- Future of Education 7

- Future of Energy 8

- Future of Finance 19

- Future of Food 6

- Future of Housing 3

- Future of Humanity 22

- Future of Retail 9

- Future of Sport 1

- Future of Transport 8

- Future of Work 10

- Future society 11

- Futurism 20

- clippings 1

Archive Note

The archive of posts on this site has been somewhat condensed and edited, not always deliberately. This blog started all the way back in 2006 when working full time as a futurist was still a distant dream, and at one point numbered nearly 700 posts. There have been attempts to reduce replication, trim out some weaker posts, and tell more complete stories, but also some losses through multiple site moves - It has been hosted on Blogger, Wordpress, Medium, and now SquareSpace. The result is that dates and metadata on all the posts may not be accurate and many may be missing their original images.

You can search all of my posts through the search box, or click through some of the relevant categories. Purists can search my more complete archive here.